Since the introduction of mathematics in its rawest form in Ancient Greece, mathematical knowledge has since been revered by all for its quality of objective truthfulness. But it is not as simple as it seems. There are already many issues with objective truthfulness when one analyses the origins of mathematics itself: the axioms. In this essay, however, I will talk only about another aspect which seems to rock the seemingly solid foundations of mathematical proof – time.

When asked if mathematical truth is time dependent, our immediate impulse is no. To be sure, we recall the changes in standards of truth in natural sciences; there was a Copernican Revolution in astronomy, a Darwinian revolution in biology, an Einsteinian revolution in physics, and even a Kantian revolution in philosophy. At first, when we look at mathematics, we do not see any semblance of revolution to have occurred; it seems that unlike other sciences, where one generation tears down what another has established, mathematics alone has each generation building a new story to the old structure established by previous generations.

Yet one only has to dig a little deeper to find several major upheavals in mathematics. For example, the axiomatization of geometry by Euclid in Ancient Greece transformed mathematics from an experimental science into an intellectual one. Furthermore, the discovery of non-Euclidean geometries (such as elliptical geometry) in the 19th century led to the realization that mathematics perhaps lacks meaning in itself, and that it is merely a logically connected study of abstract systems. These are just some examples of ‘revolutions’ in thought that changed the view on the nature of mathematical truth. In order to comprehend these changes and understand why they happened, I will first show that changes did in fact occur, and then we may answer the question posed in the title.

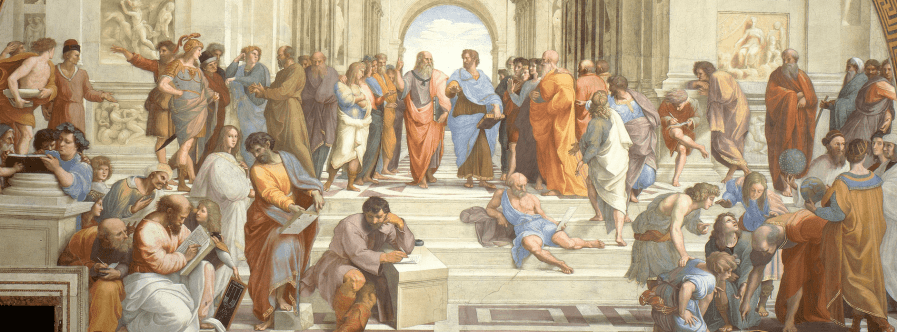

The simplest and earliest significant revolution can be seen in the contrast between Egyptian and Greek mathematics. Let us first establish the Ancient Greek perspective of mathematics. One fact which is often overlooked is that the Ancient Greeks are the ones who invented rigorous proofs. At the mature stage of Greek mathematics – the time of Euclid, Archimedes, and Apollonius – an incredibly high standard of rigour was achieved. One possible and likely reason for their attention to rigour is the emphasis on intellectually rather than practicality in Ancient Greek civilisation. On the other hand, the Egyptians were less attentive to detail, so much so that they equated the area of a circle to the area of a square whose sides were of the circle’s diameter. From this perspective,

becomes

, a value which is around

off its true value. Why is this? The Ancient Egyptians simply did not care about details. For the purposes of Egyptian engineering, this

error was unimportant; otherwise, their impressive monuments would have collapsed long ago. Of course, as civilisation advanced, the Egyptian crudeness in mathematical expression would diminish, as the Ancient Greek rigour became the foundations of modern mathematics.

The previous paragraph outlines a very crude and extreme revolution in mathematical proofs; thus, let us turn to a more recent time – the Newtonian era, the 18th, and 19th centuries. The first decline of the high standard of mathematical rigour in proofs appeared with the invention of calculus. The most basic fact of calculus, the derivative, while it is completely intuitive to anyone who learns it, lacks significant foundations of rigour at the time of Newton.

(The gradient of the tangent at is the right-hand-side of the equation, as

approaches ).

Indeed, the mathematician reading this may already understand the issue: what does a number “approaching” another really mean? 19th century French mathematician Cauchy would later quite successfully rectify this issue, but at the time of Newton, he was unable to rigorously (by modern standards) prove the property. Nevertheless, he used it anyway, as it opened up a new dimension to physics and astronomy. Newton was wholly aware of the uncertain predicament of calculus at his time, which perhaps explains why he hesitates to use it in his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, instead opting for the grounded geometry of the ancient Greek. However, the discovery of calculus is perhaps the catalyst for the revolutionary push for results rather than rigour in the following 18th century.

Now we come to the incredible revolution of the 18th century, where the importance of rigour is replaced with the insatiable drive for mathematical results. Let me illustrate this with an example from Leonhard Euler. His theorem (now proved) states that:

(Left-hand-side is sum of reciprocals of perfect-squares)

His analytical “proof” was in no sense rigorous; his method of proof was not yet established rigorously until much later, and at that time it could only be confirmed to 30 decimal places, which apparently made it indisputable. Now, this proof would almost seem like a rather primitive approach in modern mathematics, but as aforementioned, to the most prominent mathematicians of the 18th century such as Leibniz, Bernoulli, Taylor, and Euler, results were of utmost importance, not rigorousness. But what is it which led them to believe this?

A possible reason is that mathematics participated in the Scientific Revolution, where finding new knowledge becomes the major goal of all sciences. Indeed, in 1545, the first major result for mathematics came in the form of finding the solution to the general cubic equation. The invention of calculus at the close of the 17th century only increased the almost maniacal fervour for new knowledge, for it provided an incredibly powerful way that promised vast new worlds to conquer, especially in physics and mathematics. By the 18th century, the mathematical minds at the time realised that there was a great vacuum in mathematical knowledge, and quickly moved in to uncover it. It is almost as though the mathematical world has flipped itself on its head: before the 18th century, the means justify the ends; within the 18th century, however, the ends justify the means.

In the 19th century, however, this drive for mathematical results calmed, and a new realisation hit; despite the numerous results of the 18th century, much of them lacked rigour in their proofs. Yet what perhaps unsettled prominent mathematicians of the 19th century such as Cauchy the most is the fact that many mathematicians left their results as approximations – and left it there, as approximations, to pursue more novel ideas. Let us take the integral in mathematical calculus as an example. The integral (area under the graph, bounded by ) was only approximated by 18th century mathematician Leonhard Euler using a sum, which was not just inaccurate, but extremely tedious and time-consuming. Cauchy came along and looked at the problem from an entirely new point of view. Instead of trying to calculate the definite integral with a sum, he defined the definite integral as the limit of the sum (which gives the exact value) and used this to prove the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus (recall that this was unproven at Newton’s time).

This example is one of many, where 19th century mathematicians such as Gauss, Cauchy, Abel, and Weierstrass sought to prove previous results which were either left as approximations, or were left ‘proven’ without appropriate rigour. We thus see a clear shift in perspective; mathematics in the 19th century not only requires results, but clear definitions and rigorous proofs. Of course, individual mathematicians at that time may still concentrate on discovery of creative methods and ideas to be exploited, but they can no longer be indifferent to rigour when presenting their proofs, or else those ideas may not be heard at all.

We have now seen how attitudes towards mathematics changed with respect to time, and are now left at a point of indecision: what should a mathematician do, knowing that such re-evaluations occur?

We may take a rather negligent approach, where rigour may be placed at a lesser importance than other aspects, such as obtaining mathematical results. But then we would have no Cauchy series, for Cauchy would have been better off focusing on his engineering career than his mathematical one.

Alternatively, a hardliner approach is possible, where the highest standard of rigour is required at all times. Then Euler would never have written a line of mathematics. Furthermore, Cauchy, Weierstrass, and Taylor would have had no results to refine, no mathematics to build upon.

It seems we may have found ourselves in a dilemma here. However, there is a third possibility. Perhaps mathematics grows not only by successive generational increments, but also by the occasional revolution. In order to have a future where improvements can be made to mathematics, we must accept the possibility of present errors. Therefore, perhaps to the dismay of many, and myself even, mathematics is not the unique science which deals with absolute truths, one which does not have revolutions. To those readers who find themselves troubled, perhaps you may find consolation in the fact that most of the old bricks will find some place of their own in the new post-revolution structure.

good read, keep this up

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good read. One thing I find interesting is that some of the biggest advances in mathematics have come from mathematicians finding new ways to approximate, like Taylor’s series. And interestingly how that can be used to prove precisely that the sum of the reciprocals of squares is pi^2 / 6.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Keep up spitting the fax m8, Michael Jiang is still my favorite mathematician

LikeLike