The following is a summary/reflection written during my study of the historical development of jurisprudence through Henry Sumner Maine’s Ancient Law. It was an exciting and rewarding read, hence this piece of writing. It’s also probably a bit more disconnected than usual, since Maine weaves together a large variety of ideas within short paragraphs and I had written it while following his train of thoughts. Nevertheless, I hope some of these fascinating ideas remain clear in my writing.

According to Maine, all societal legal developments follow these 3 epochs in this order.

The Epoch of Divine Judgements

All the known successful judicial systems began with judgements, which evolved into customs, before being consolidated as codes. Judgements are the first jural phenomena of human societies, and the earliest of these key phenomena are recorded in Sanskrit literature and Greek Homeric epics, which detail moral and metaphysical conceptions that serve as the source from which all forms of law emanate.

In ancient societies, a supernatural primacy consecrated and upheld the cardinal institutions of state and family. Homeric jural conceptions, as embodied by the words Themis/Themistes, were heroic-aristocratic/heroic-monarchical notions of justice that were contingent on divine inspiration at the moment of adjudication. So called because it was through the pre-eminent figures of hero-kings like Theseus that justice was dispensed. At this stage, these instances of adjudication do not represent “law” as we know it, but remain isolated judgements. But, over the course of generations, parities in facts and circumstance naturally gave rise to similarities in judgements, which then led to the development of nascent legal customs, known in Greek as Dike.

This age of individual judgements and vague legal customs reflect the reality that ancient societies were controlled not by clearly defined notions of right and wrong or rigorous legal systems, but by the caprice of the patriarchal despot. In the state it was the warrior-king, just as in the family it was the father, whose autocratic dictates maintained order between individuals. Whereas true law as we know it enjoins upon all citizens indifferently a number of rules and acts similar in class and kind, judgements and customs were nebulous threads that upheld existing dynamics and structures. The legitimacy of these judgements was rooted in the supereminence of strength, courage, and wisdom in individuals who were given divine prerogatives, or, more precisely, might.

The Epoch of Customary Law

As societies grew in size and complexity in the Western Axial Age, political and military oligarchies/aristocracies gradually assumed monarchical functions as societies developed, rendering the heroic-king mostly symbolic and sacral in their responsibilities. The kings of Rome were overthrown, and their authority was divided among the elected consuls and praetors. The kings of Sparta became nothing more than hereditary military officers, just as the kings of Athens were supplanted by assemblies and archons. These new aristocracies served as the primary depositories and administrators of law as it existed in its infant form.

Because this political development coincided with the maturation of legal customs, the new aristocracy drew on the accumulated aggregate of customs and observances which they monopolised rather than pretend to receive divine inspiration at each individual moment of judgement to render justice. Although this unwritten jural system was often susceptible to abuse, collective memory of traditions and customs served as a limited, but sufficient counter balance. In terms of fairness and stability, it was an upgrade to the kingly system of judgements.

It must be noted however, that this period of development is much more distinct in the West. This is because in the East, this political/military oligarchy tended to move towards a religious function, whereas in the West this power remained wholly legal. This difference will be very important in the upcoming Epoch of Codes.

The Epoch of Codes

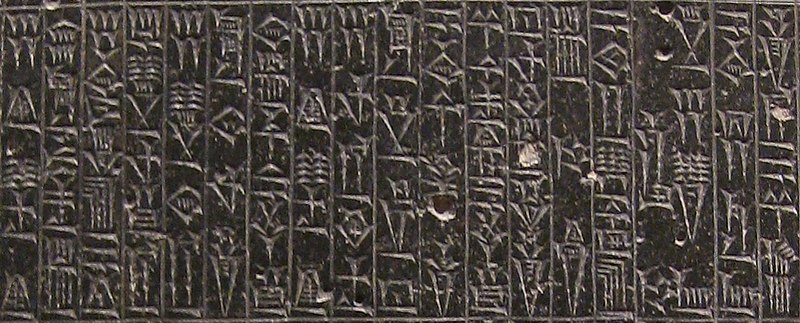

In the West, as the masses successfully challenged the oligarchy at each stage of societal development, codification of the law progressed steadily. By the 400s BCE, most Mediterranean states had come to be ruled by farmer warriors with a prominent political class. This is distinct from the divinely sanctioned aristocracy that succeeded the hero-kings of the Bronze Age. This can be clearly identified in the transformation of the Roman societal structure, in which ancient patrician households were assimilated by plebeians. Although the Roman Senate retained some traces of the absolute aristocracy that preceded it, by the 400s and 300s it was not a hereditary class of nobles but a congregation of economic and political leaders. With this political development, the customs and observances that the aristocracy once monopolised began to be written down as codes, some famous examples of which were the Twelve Tables, created in 450 BCE, and the Code of Solon, created in 610 BCE. This development was enabled by the invention and proliferation of writing as well as the increasingly sophisticated structure of farmer-warrior societies.

Crucially, codes popularised legal knowledge and introduced greater security and stability to jural principles. Society became more immune to frauds, misused legal analogies, and the degeneration of national institutions. The function and power of aristocracies thereby gradually transformed and weakened. A level of equality was introduced to societies in this way, consolidating a body of rules and institutions best suited to promote the community’s physical and moral well-being. So long as the integrity of this body is preserved until new social wants add novel practices to the existing legal knowledge, the upward march of civilization is almost guaranteed.

In the East, it was a different story. The aristocracies of India and China consolidated their political, legal, and military monopoly with religious power. Thus, Eastern “codes” such as the Laws of Manu (Hindu Code) were not democratised legal knowledge but aristocratic aspirations of law. This form of persistent agrarian legal despotism gave rise to the Caste system that enabled the corruption of legal thought and societal institutions for the sole benefit of the aristocracies.

Without legal codification, the aristocracy were be empowered to place a stranglehold on societal progression and freely prevert principles and institutions through the manipulation of jurisprudence. This is perhaps why Eastern civilisations tended to periodically stagnate where the West progressed with greater haste.*

*I do not fully agree with this point, but it is very interesting to look at this East-West distinction through Maine’s perspective as a 1800s British lawyer and legal officer who had once governed India for the empire. His analysis is almost purely legal and so retains its merit, hence its inclusion here.