The notion of meritocracy – a societal system in which people are selected on the basis of their demonstrated abilities and merit – has been thoroughly, and for many unknowingly, ingrained into Western society and political structure. In the Western capitalist democracies, efficiency is integral to maintaining consistent advancements both technologically and economically; the premise to sustaining such efficiency is a system which accounts for the inherent and natural drives of mankind, namely, selfishness. By accounting for such psychological factors in attributing concrete values to intellectual possessions of mankind (which are entirely ‘unstealable’), meritocracy, in general, has accelerated intellectual progress. However, in doing so, it has created unintended consequences, adverse and beneficial both in a local and global context. Before analysing the effects of meritocracy on academia and technological progress, however, it is important to first consider both its contemporary socio-economical-political context as well as its historical development.

Perhaps the best way to illustrate the distinct culture which meritocracy creates and nourishes within society is through a historical analysis of Imperial Chinese and British societies. Both known for their strict traditional hierarchies and societal norms, these two empires have coexisted for over a millennia, with contrasting origins, different ideologies, on the opposite ends of the world. Like branches of a tree spreading out in opposite directions, Chinese culture and tradition throughout its history has shifted away from the pre-civilisation pragmatism towards a far more philosophical and merit based society. Indeed, Confucius himself at around the 6th century BC has laid the foundations of meritocracy and articulated the strengths of a government whose representatives rule by merit instead of inherited status. While circumstantial evidence suggests that such a system already underlies Chinese society at the time, the Han dynasty certainly adopted such a Confucianist service system, where the Chinese bureaucracy selected its representatives based on examination, as well as an assessment of their character. While Chinese meritocracy has continued on a generally constant trajectory even to the modern day, the post-Roman West, especially the British Empire, began an ultra-traditionalist and hierarchical approach in defining its societal structure. Where China bases people on merit, the British refer instead to familial influence – such restrictiveness indicates a static social order, which stands in contrast to China, where one has the possibility of gaining influence for their family name through their intellectual abilities. With such a stark contrast in culture and tradition, surely their respective ethical structures must similarly differ. Indeed, Ancient Chinese often placed a heavy emphasis on the knowledge of elders, from which the moral value of respect arises. In the West, respect also possesses moral value, though for different reasons, and to a lesser extent; the hereditary and aristocratic backbone of their society places respect as important not because of its importance in maintaining the value of knowledge, but rather as means to political and monetary ends. Comparing the 19th and 20th century Warlordism and corruption within China with the full might of the British Empire, perhaps Ancient China was far too premature for merit to take on such an important role in societal decision-making – that may be for a future blogpost. For now I am interested in the influence of meritocracy on both the definition and prevalence of happiness, which in turn, along with other factors that stems from a merit based society, influences development of academia and progressive thought.

With meritocracy quickly rising in prevalence and extent in the politically diverse modern world, one of the simplest, oldest, and yet simultaneously most complicated notions in the history of philosophical thought – happiness – has transformed; its meaning has begun to branch out subtly and multi-dimensionally. To establish one end of the effects of meritocracy, one may observe modern Communist China, which has carried on the strict merit-based policy that it adopted two millennia ago. As someone who has visited China and who comes from such a culture, what is perhaps most astonishing to me is the mingled coexistence of the state of happiness, and the possession of merit. In other words, the idea of using merit as a currency for determining the capabilities of a person is so ingrained in the social and beaurocratic framework that the happy life has been intrinsically linked to the possession of appropriate merit – happiness therefore has become nearly equivalent to the degree of various merits which one possesses. At this point, one may be confused as to why there exists such a disparity in ethical definitions between the modern east and west, given that merit is also a fundamental aspect of the capitalist system. However, the key difference that must be noted is the difference in the respective political and economical contexts; one is a capitalist democracy, and the other a dichotomous mixture of autocracy, Marxism and capitalism. Such a combination of liberalism and meritocratic capitalism in the West implies that other important aspects of human society is not completely overshadowed by the necessity to work and achieve; a delicate balance is being maintained in order for society to remain free, yet be incentivised towards furthering academia. Thus, in a liberal-capitalist society such as modern USA, while happiness is linked with merit, it does not necessitate it; conversely, merit does not guarantee happiness.

Now that the definition of happiness has been established to be dependent on other factors such as politics, one may ask, at this point of the blogpost, how this links to the rate of development of academia. The ramifications are subtle and understated, yet significant and surprisingly prevalent. Let us jump back in history to Ancient Greece, and consider what exactly made it the so called ‘cradle of civilisation’. While the society is now dubbed a meritocracy, there are certain debates around the extent to which it was really implemented. We shall bypass such debates and focus instead on the effects of the general acceptance of the idea of building a society upon meritocracy at that time. Athens was one of history’s very first examples of liberalism, where freedom of speech was valued, and from which numerous revolutionary philosophical and scientific ideas ( such as Platonic idealism and the axiomatization of mathematics) sprung forth, much of which are still studied today. Even though the elites were separated from the common people in terms of estate, wealth and power, there was a general emphasis on qualities such as intelligence, morality, and work-ethic. (There even exists evidence of such a culture continuing to exist in Rome – the Rape of Lucretia serves as a prime example of how work-ethic has not only continued to be valued, but even as a quality that is idealised). Such a fixation on these idealised moral qualities, combined with the liberalist political approach, eventually led Athens to what it was famous for – a fountain from which literature, philosophy, mathematics, and all other academia developed and prospered. One can say, meritocracy leads man to the door, and freedom of speech unlocks it. What has therefore been established is that with an appropriate balance of meritocracy within a society and freedom of expression, academia would almost certainly flourish.

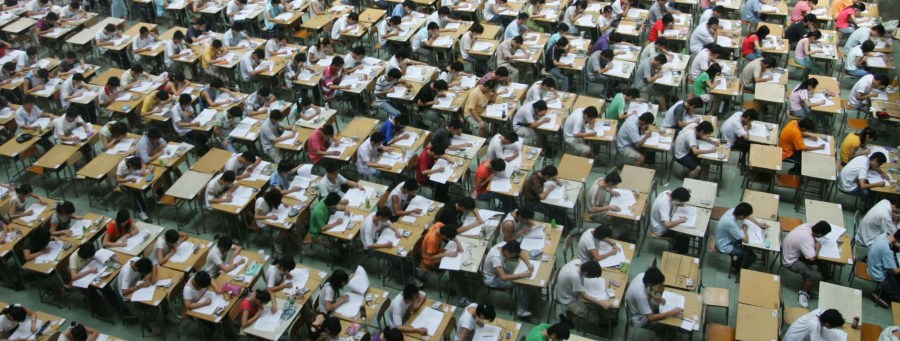

Contrastingly, in the later Roman Empire, Hypatia, a pagan worshipper, was stoned to death without trial, which exposed to the modern historian the manifestations of a new dark age in non-theological scientific and philosophical thought. The foundations of the ethics such as respect for knowledge and intelligence was overwhelmed by religious dogmatism, and efforts on the objective sciences and philosophy transformed into futile endeavours to prove existence of theological objects. As such, scientific and philosophical works were mostly dominated by Islamic authors in the following millenia, who were largely sponsored rather than oppressed by the state or religious institutions; Islamic scripture generally held the sciences as a way to appreciate and describe God’s creation. Their great works such as the magical symmetry of Baghdad, the geometric perfection of the Dome of the Rock, and the sheer impregnability of the Aleppo citadel stand testimony to the success of their use of religion not as a means to obstruct but rather to amplify academia. Further, unlike the Dark Ages in Europe, where academic progress was generally stagnant due to religious doctrinism in morality and suppression of progressive research by religious and state institutions, modern China is quite the opposite, not with respect to its political structure, but in the sense that China is totally meritocratic, with the Confucianist notion of ‘merit, not inherited status’ having been integrated almost entirely within its cultural and morality. Like the later Roman Empire and the West during the Dark Ages, the Communist Dictatorship of modern China has at least partly impaired the entire nation’s academic development, for much of the ‘input’ of thought has either been obstructed or entirely erased due to political considerations, or utilised inefficiently or insufficiently due to excessive interference of political agendas. Perhaps the most significant occurrence of such a phenomenon is the Cultural Revolution, which was devastating not only for Chinese history and tradition, but also reversed centuries of philosophical and scientific thought and culture. However, its greatest impact was that it set a hardline rule for future leaders to follow – political ends take priority over academia. Such a maxim, along with the ‘total mobilisation’ of education caused by the sheer totality of meritocracy in Chinese society, has created an almost self-feeding mechanism in the entire framework of Chinese education; students work hard to achieve merit which are politically defined rather than academically. The academia taught to school are altered for political ends, and the government inefficiently utilises the skillsets of those who have achieved the highest academic merit, instead inappropriately urging them to pursue political careers for political ends. In essence, the benefits which meritocracy brings in furthering intellectual thought and culture are reduced, if not entirely nullified, when applied grossly unproportionately to a society, with respect to the political structure and context of a state.

What has been ostensibly shown in the comparison of these ancient and modern states is that when applying meritocracy to society, it must be applied in suitable proportions, with an appropriate accompanying political structure, in order for people to live freely and happily, which in turn indirectly but vigorously advances academia. The earlier ethical considerations with regard to meritocratic societies has shown that while freedom or happiness in a liberal society is not a necessary factor to intellectual progress in a meritocratic society, it is a key step in maximise it. Totalitarian states therefore reduces the efficiency of the advancement of academia, for they restrict freedom, comingle research with politics, or both. Ultimately, what I believe must be understood is that academic progress does not require the conditions regarding meritocracy, ideology or politics to be satisfied in order to advance quickly, but that those conditions are necessary for sustaining or maximising such rates of progress. After all, external factors such as imminent foreign threats do play significant roles in shaping a country’s short term policy. As Stalin, dictator of USSR, once said during the interwar period:

We are fifty or a hundred years behind the advanced countries. We must make good this distance in ten years. Either we do it, or we shall be crushed.

History says the rest.