Part 1: https://venividiveritas.com/2023/01/24/queen-of-cities-a-fictional-tour-of-constantinople-in-540-ad/

Part 2: https://venividiveritas.com/2023/02/22/the-queen-of-cities-part-2-house-of-god/

Without Ecritius’s presence, I was naked and alone in the grand halls of Imperator Caesar Justinianus Augustus. The courtiers, each of them garbed in silk so fine I could see the pale hue of their skin, were as sullen and silent as mosaic saints as they led me past hallway after hallway. Shadows danced on the walls as my footsteps echoed in the hollow rooms, the muffled whispers of my companions joining with the distant clamour of banquets in a perturbed cacophony.

When I was yet an aspiring youth in the nascent years of my career, I accompanied my uncle on his trip to the palace of Theodoric Rex–the then-patrician and governor of Italia by grace of Zeno Augustus–in fortress Ravenna. There, surrounded by swamps and mires and walls of stone, was the greatest structure I had ever seen: a grand palatial residence filled with the voices of men and the din of arms. Upon a gilded throne sat the lord of the Goths, Theodoric, Bane of Odoacer, thundering royal commands. His furled brows, gleaming eyes, and towering stature invoked memories of the forgotten Hellenic gods whose faces once lined the shrines of my home, clasping in their hands bolts of lightning and three-forked tridents, figures of rage and terror. And yet, my knees did not quiver in his presence. I knew, even then, that beneath the royal regalia and golden crown was but a man, endowed by God with a task greater than my own. The palace, for all its grandeur, was his home, a place where his family and retainer lived and breathed, performing their duties as the rulers of ancient Ausonia.

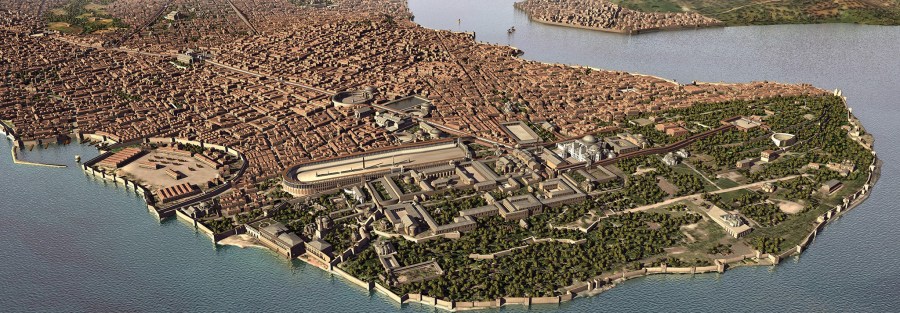

Twenty years hence, as I walked the winding corridors of Palatium Magnum, my boots falling upon grounds ruled by Romans, my people, there was only dread in my frantic heart. Theodoric’s dwelling was warm, humid, and filled with the smell of steel and wine and freshly baked bread. His men drank and ate and laughed as my uncle conversed with their chief at the high table. Although I knew not their tongue I could feel their hearts, beating, same as mine. But there, within the palace built by Constantinus Augustus himself, I sensed no such kinship amongst my companions who shared my tongue, my allegiance, my culture, and my God. The weight upon my chest had returned, crushing me as the hallways grew larger and darker with every turn, expanding further beyond the boundaries of human reason. The palace was not a single building, but an enormous complex which dominated a third of the City’s landscape. To my left I recognised the Magnaura—red bricks and bronze dome—which housed the Senate. Although I myself can be counted amongst the senatorial ranks in Rome, I knew that there was no place for my kind there. I have heard that the magnates of Constantinople habitually squander gold bribing officials of the palace for a place amongst the senators, lavishing gifts of slaves and exotic treasure to be included in the invitation lists of imperial banquets or be seated closer to the Augustus himself.

Dwarfing the Magnaura was the Triclinium of the Scholae and the Triclinium of the Excubitors: grand, spacious structures which housed the barracks of the palace guards. The sworn blades of the Augustus were as silent as the courtiers as we passed, their gaze distant and misplaced as if in prayer. Behind those imposing buildings was the Palatium Magnum itself, black against the red light of the fading sun, its shadow cast over our heads like a night sky without stars. But thankfully, it was not my destination for the night. My small retinue turned as we approached the palace proper, heading to the source of the once-distant clamour—the Triclinium of the Nineteen Couches.

The feast had already begun when I set foot in the reception hall of the Augustus. Highborn men and women were propped up on silk pillows as servant girls slithered between the tumefied masses of their gold-clad bodies, carrying trays of dishes I could not name. Although there were no less than two dozens guests, I heard no laughter, only words, drifting in the torch-lit hall, reaching my ears as meaningless dribble. A few cast unassuming glances at me, but none took notice of my entrance. My raiment, the finest set in my possession, condemned by the bishop of Barium himself as a wanton display of excess and immodesty, appeared penurious in the presence of my fellow guests. Unsure of my recourse, my eyes wandered the room in search of my host.

It did not take long for him to be identified. Ioannis of Cappadocia lied reclined on a raised platform, holding in one hand a golden cup studded with the largest rubies I had ever seen, and in the other a comely slave girl adorned with more jewellery than Theodoric himself. Noticing my gaze, he turned, frowned, and twisted his fat, swollen lips into an soft, foetid smile.

“Come, emissary of Magna Graecia, take your place amongst the loyal servants of the Ever Augustus,” the praetorian prefect spoke with a winding, nasal voice, indicating to the gilded silk couch poised next to his own.

I did as he commanded, lying down on blankets softer and lighter than the clouds. After a formal exchange of greetings, he dismissed the girl, and leaned in to such hateful proximity that I could smell the spices in his breath.

“Tell me, Symmachus of Barium, how fares Magna Graecia in the war?”

I looked into the watery sapphires of the praetorian prefect’s eyes and swallowed. What was I to say? Thousands of my countrymen had fallen victims to Gothic blades, a dozen towns were reduced to cinders, and starving farmers choked the streets with their emaciated cattle and families, seeking shelter behind city walls. They knew not who they were fleeing from: Romans or Goths, men of war are alike in their brutality. The Appian Way, once the central artery of Italia, lay in morose silence: a twisted, abandoned path snaking through rubble and deserted farmlands. Every spring, the Romans would drive the Goths back to the north, their forces bolstered by reinforcements from the Orient, and every fall, the Goths would return with Frankish warriors, scorching the fields as they went. Every year, the cycle repeats, and thousands more are buried. Rome itself, I heard, has changed hands no less than six times. Now it is nothing more than a burnt, hollow shell, inhabited only by the dying and the dead. Was it my duty to speak of these sufferings so that I might see tears in those large, unblinking eyes? Should I bid the praetorian prefect weep with me? How could I put these horrors into words of eloquence fit for the dining hall?

I surveyed the Triclinium, filled with the scent of musk and perfume and spices and wine. Dozens of men, plump with joy, sat feasting on a meal fit to feed hundreds. Within their fat, swollen hands they hold the power of a hundred legions and a thousand ships, and yet they use them to hold wine cups and slave girls. These are the men who decide the fate of my city, my country, my people. How could they ever understand? Had they lain eyes upon rotten, maggot-filled bodies? Do they know the stench of death? How could they? The sweet fragrance of incense and perfume, overwhelming to the senses, was all that they could smell. The pretty little slave wenches, with their silk-clad, gold studded bodies, was all that they could see.

And so I turned to Ioannis, words that I never thought I would say emerging from my mouth, “I cannot answer your question, Ioannis, but I can ask one in return: why did your legions land on our shores?”

I expected anger, horror, or at least some uncertainty, in reaction to my abrupt break with decorum: I was a mere emissary, and he was the praetorian prefect, appointed by the vice regent of God himself to oversee the empire. But he merely grinned, proudly displaying his sallow teeth. “‘Our’, ‘your’, amusing choices of words,” he spoke in a soft nasal whisper, “we are the Romans, my friend, united by the Will of God, who had Himself commanded us to expel from Christian soil the filth of barbarian heretics.”

“No matter the cost?”

“What, Symmachus of Barium, are gold and men compared to the will of our lord?”

“And which lord is that? Justinianus or Christ?”

He said nothing, but his eyes told me what I already knew.

…

The crimson hue of the sun had long faded when I stepped out of the Triclinium, replaced by the pale glimmer of a crescent moon, curved and sharp as a Hunnic knife. The banquet was yet to conclude—Ioannis had promised me that it would continue long into midnight—but I could not endure it for a moment longer. The silent palace grounds and the cool breeze of the night was accompanied by a soft and gentle rain, shrouding me in a quiet drizzle. I stood unmoving as the water washed over my body, cleansing it of the stench of perfume and eastern spice. I knew then why it was I whom Magna Graecia chose for the task. Forty years of age and without accomplishments, I must pay the price of mediocrity with my sanity, offered up as a sacrifice for the Palatium Magnum to devour. Beneath me, at the foot of the hill upon which palace stood, I could see Constantinople, the city of New Rome, stretching out as far as my eyes could see. Five hundred thousands souls, asleep and breathing in harmony. Beyond the dozens of cathedrals which slumbered in the gloom, I saw the Theodosian Land Walls, with its seventy watchtowers: silent sentinels looking out into Thrace, each of them so tall I thought they joined with the heavens. How, could men ever hope to breach these walls? What would it take for this city to fall? What is there for the Augustus to fear? Attila, at the head of an indomitable Hunnic horde, had once swept away all the armies of Romania. Arriving at the gates of Constantinople, he ordered his men to storm it by force. Now, his body lies rotting beneath the earth and Fortress Constantinople remains as it was a hundred years ago, impregnable.

“Wondrous, isn’t it?”

Startled, I looked to my side I to notice a quiet figure, his hands hidden in the long sleeves of his garb. The man was short, bald, and fat, and even though his face remained obscured by the shadows, I could feel the faint smile on his lips.

“Apologies, senator,” he stepped out into the light, revealing a smooth, beardless face, “but it was not so long ago that I myself partook in this same activity. Gazing upon the City with kings and gods and wars on my mind.”

I turned to face him, perplexed, for I had not seen him at the banquet. The man was clad not in gold and jewels and silk, but a simple, yellow robe. His Latin was perfect, and his eyes were filled with something so very familiar.

“Greetings, I am Symmachus of Barium,” I spoke with a tone friendlier than most, “forgive me, but I don’t presume that we have already been acquainted?”

“I am afraid not, my friend,” he replied in his soft, flowing voice, “the role of a eunuch is to remain unseen until he is needed.”

Eunuch. That explained his demeanour and his voice, but it revealed not the purpose of his visit.

“And what might you be needed for now?”

“To meet a guest of honour,” his smile was sly, but somewhere in those smooth, unwrinkled lips I thought I saw a flicker of integrity, “you came here for those who can change the fate of your city and your country, but found only fat men drunk with girls and wine. You know as well as me that you will not find what you seek here.”

“And what do you propose?” My voice was laced with the bitterness I failed to conceal, “sail back to Magna Graecia and watch my country burn?”

“No, that would be cowardice, unbecoming of a man as eminent as you. What I was told to offer you is the opportunity to speak your mind to someone who can grant you your wish.”

“And who might that be?”

“Come, and you shall see.”

And so I did. I knew not how the eunuch knew my name and my purpose there, but whoever his master is, he must be a man of great influence. It would not have been diplomatic of me to refuse his invitation. Plus, I would do anything to delay my return to Ioannis’s side in the Triclinium.

The eunuch walked in the dark without the aid of torchlight, and I followed, navigating unlit corridors and serpentine paths until we at last arrived in front of an unassuming brick wall. He stopped, moved his large, smooth hands along the solid structure until he snatched something in the corner.

To my astonishment, the wall slid open like a door, revealing behind it a winding stairway. I suddenly realised where we were: he had led me to the base of the Daphne Palace, built by Constantinus himself more than two hundred years ago when he first founded the city. Now, it is the residence of the imperial family.

Up the spiralling staircase I went, laboriously lifting the heft of my body up the steep inclines. Who was I to meet, someone with the power to supercede a praetorian prefect? An advisor of the Imperial Consistory, perhaps. But what was it about me that could interest a man of such status? Questions swirled in my head as I endured the slow torture of ascent. After a handul of breaks to catch my breath, I emerged into a hallway, alight with gilded lamps and covered in Persian rugs. Portraits of saints and sovereigns past greeted me as the eunuch led me beyond a large, mahogany door and into an adjacent chamber.

There, at the centre of the most spacious room I had ever seen, stood a woman, her slender body wrapped in a garment of deep, purple hue.

Tyrian purple, the dye of kings.

Before I could decipher the meaning of her dress, my eunuch guide abruptly prostrated himself on the floor in front of the woman, like a supplicant in front of Christ’s shrine. He leaned in with his round, pale head, and kissed the woman’s scarlet boots. Crawling back, he stood up with his head bowed, and uttered, “Domina, Symmachus of Barium is here.”

When rumours cross the Adriatic, travelling from Constantinople to Italia, they change hands at least a dozen times, passing from sailor to sailor as they go from port to port along the jagged Aegean coast. By the time they reach our ears they are more often than not distorted beyond recognition: a small riot becomes a second Nika revolt, a small victory becomes another Battle of Darra. So, when word reached us that Theodora, wife of the Augustus, crowned as Augusta in the fabled Hagia Sophia by the Patriarch himself, was the daughter of a bear-trainer and a well-known harlot of the brothels, we dismissed it as yet another unfounded lie. She probably just had covert affairs, we told ourselves, or she just looked too pretty to be faithful. And yet, year after year, tales of her former exploits continued to sail the Adriatic to inundate our halls with unholy murmurs, each of them wilder than the last. One man once told me that the Augusta was known to have enjoyed copulating with twenty men at the same time, and would wear all of them out long before she herself was satiated, compelling her to turn to cattle and horses and pigs to satisfy her perverse desires. Another swore by his name that Theodora was once heard to have loudly complained that God did not grant her enough holes, for three is far too few, and so she prays daily for two more on her breasts. A fellow senator and a trusted friend of mine, upon his return from Constantinople, said that Theodora was known to have accompanied her sister since the age of thirteen, carrying the bench upon which she would sit to attract customers. Although she herself was yet too young to engage with men in the conventional way, she would offer forbidden union to any who did not fear the fate of Sodom. All of them, however, spoke not in jest or disgust but in awe. Theodora: the daughter of the brothels who became the Augusta of New Rome.

That very woman of legends was standing before me, in that room, having invited me into her chamber in secrecy. She was not clad in full imperial regalia, and her hands and neck were adorned with only a scarce few pieces of jewellery, but for the first time in my life, I felt a presence greater than my own. She was short and slim, her hair bound up in a dignified mass, but within her dark, obsidian eyes there shone something I had never seen. Ambition? Hunger? Hate? Amusement? For all my experience in the senate, I could not know for certain what story her eyes told.

Suddenly, manners jolted back into my body. I had been instructed a dozen time over that if I ever found myself in the presence of an imperial personage, prostration must be performed so that I may kiss their feet lest I suffer grievous punishments. Laboriously, I willed my stiff joints to bend in my best imitation of a proskynesis.

“Don’t bother,” the Augusta interrupted me before my belly could touch the floor, “if I wanted to exchange manners I would have summoned the Cappodocian. You are here because I want to know what your eyes have seen, and what your ears have heard.”

“Domina,” I bowed, a burning sensation filling my stomach, “my eyes and my ears are at your service.”

“Then prove it, with words of unblemished truth,” her voice was a knife, cutting deeper with every word, “how fares Magna Graecia in my husband’s war?”

And so I did, with words as pure as alabaster stones I sang of my countrymen’s suffering. I told of the burning cities and deserted fields, and of the empty halls of forgotten Rome.

By the time my had concluded my tale of sorrow, the glimmer in Theodora Augusta’s eyes had changed yet again. Was it concern? Grief? Rage? I questioned in vain, for her face remained an unmoving visage of majesty and beauty.

“I beg of you, Augusta,” I spoke again, failing to conceal my desperation, “conscript not my countrymen and tax not our cities, we have nothing left to give. All had already been taken.”

She gazed at me in silence. The eunuch had disappeared, and I was alone with her in the room at the beating heart of New Rome.

“What do you know of Nika?” She asked, breaking off her gaze to walk the room.

“I know only that it was a shameful act of unjust usurpation, domina.”

“Shameful? Unjust? Symmachus of Barium, how could they not? What would sovereignty mean to you if you could not feed your children and tremble in fear of death everyday? I sensed the revolt long before it began. I smelled it on the streets and I saw it in the people’s eyes. It was the same look I once saw in the mirror when my father passed.”

This time, although her back was turned against me, I knew what glimmered in those eyes.

“When the rioters burned down the Augusteion and besieged the palace, my husband ordered ships to be readied for our escape,” she continued, “and all the wise men of his consistory nodded in agreement. For all his intellect, Petrus does not know the hearts of men. He sees only maps and laws and armies, not the men behind the scrolls and the words. The dream of Rome is the bane of man. It is my duty as wife and Augusta to bind him to this earthly kingdom, to teach him the ways of the world that he rules. I have known so many men in so many ways, and through me he shall know them too. I knew that power, once lost, could not be regained. Exile and ignominy is a fate worse than death, and the imperial purple makes the best burial shroud. And so the next day our men marched out of the palace and into the Hippodrome with swords in hand. Thirty thousand souls passed that day, all because I failed to intervene when I still could. I swore that day, as Theodora of the brothels, that it will never happen again.”

She paused, and turned around to face me.

“There is something in the air, something terrible beyond imagination, I can feel it every night, pulsating,” She approached with a pace faster than I expected until she was close enough for me to smell her. She wore no perfume.

“So yes, Symmachus, I will help your people, but there are those who still resent my influence and plot my downfall. Be my agent in the palace, be my ears at banquet halls, and be my hand when I commad it, and your wish shall be granted.”

“What, my Augusta, is your command?”

Her lips curved to form the faintest resemblance of a smile, and there I thought I saw the glamour of a young theatre girl, hidden behind a gilded mask of practised regality.

She leaned in, uttering her instructions.