It is with great shame that I now admit that for the longest time I had thought my hometown of Barium to be the jewel of the world, a city unrivalled in its architectural splendour and cultural brilliance. My fellow citizens all took pride in the beauty of our city, and I was prone to engage in fierce arguments with outlanders when they did not show Barium the respect which I felt she deserved. But my recent trip to Constantinople has revealed to me the true extent of my ignorance. I should be thankful that fortune and circumstance have conspired to elucidate my folly, or else I might have departed from this world without ever having witnessed for myself the crowning achievement of mankind. It was the summer of 6048(549 AD), and as the magistral emissary of Magna Graecia, I was endowed with the unwanted task of renegotiating the taxation of our citizens with Imperator Caesar Justinianus Augustus on behalf of my city. I travelled down the length of the Italian peninsula, the once bustling Appian Way now devoid of travellers in the aftermath of the war, reaching the port of Brundisium on the eighth. The maritime town was among the few which had remained untouched by the conflict, and yet it was devoid of its usual lustre. Market stalls were empty, the streets deserted, and the city silent. The many-coloured merchant vessels that once sustained Magna Graecia with shipments of grain from Sicilia and silk and spice from Egypt were no where to be seen. In their stead war galleys flying purple banners drifted in the water, filled with men of the east, Huns, Arabs, Vandals, and Romans, bound for Neapolis.

It was no easy task finding a vessel. Many turned me away until at last I displayed my magisterial decree. Only then did I acquire the service of Stygia, a robust, if not dreary vessel upon whose ebony husk I was to spend two days languishing in my narrow and putrid cabin. Such discomfort was to be expected, travelling this time of year in the Adriatic, but the waters calmed as we approached the Bosphorus, allowing me spend the daylight hours on the deck observing my surroundings as Stygia glided along the Aegean coast. It was on the twelfth that I first glimpsed the fabled city of New Rome through the morning haze, its form obscured by a pale fog as it emerged on the horizon. With the aid of my looking glass, I could just about make out the shape of the City, with its pointed towers and marble porticoes. It was impressive in size, but at that moment in time I was ready to dismiss the legends of Constantinople’s magnificence as mere unfounded rumours, for it did not appear worthy of such excessive praise. It was large, granted, but it just barely exceeded Barium in its bulk, and the architecture lacked the intricate details which endowed my hometown with its signature beauty.

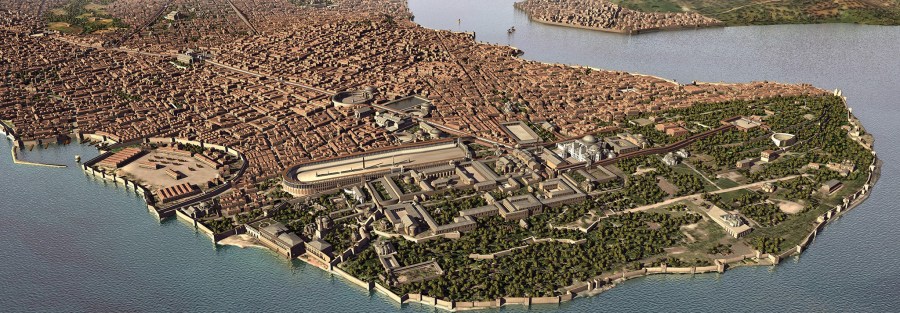

I am grateful that I kept my thoughts to myself, or else I might have been condemned to suffer jests and derision for the duration of my stay. As my ship drew closer to the City, and as the morning fog melted under the golden rays of the rising sun, I took a second, closer look of the shape on the horizon, and it was then that my mind was enthralled by an overpowering sense of insignificance and despair which writers are wont to associate with the capital of New Rome. It was with great shock that I realised that the first “city” which I foolishly mistook for Constantinople was nothing more than a small town—which I now know to be the suburb of Sycae—which guided passing ships to the City’s docks along the Golden Horn with its seven, sky-piercing lighthouses. Behind these beacons a giant slowly came into view. Try as I might, even Virgil himself could not have put into words the stupendous enormity of the structure which loomed before me. The wayshrine was dwarfed by the City proper, its lighthouses appearing like candles, inadequate against the backdrop of the Theodosian Sea Walls. Never in my life, nor in my wildest dreams, had I imagined that men could construct such marvels with the meagre tools at our disposal.

As my ship cruised through the serene waters of the Bosphorus, I saw anchored in the distant, circular harbour more vessels than I could have ever imagined, arrayed in a spiralling pattern around a single, protruding pier that led to the gate of Saint Aemilianus. I could barely conceal my urge to faint and collapse on the very deck upon which I stood when I first saw in all its overwhelming grandeur the true capital of New Rome. I had to strain my eyes to make out the distinct shapes of tops of the spires, citadels, and cathedrales within the City, each towering over the gargantuan Sea Walls. The harbour of Eleutherios itself was taller and larger than the palatial residence of Barium’s preeminent nobles. Long iron chains, each link the size of a man, held the lofty steel-banded oak doors of Saint Aemilianus in place. At each side of the open gate stood a colossus of stone and marble, carved to resemble the likeness of Crispin and Crispinian, the twin saints martyred during the reign of an ancient and impious Augustus. Between them lay a road wide enough for twenty chariots to run side-by-side, made not of rocks and beaten dirt but of red and white marble slabs. I was finally there, at the gates of Constantinople. And like a prophet graced by the presence of God, my mind was rent asunder. When the captain approached to bid me farewell he found me in a state of silent hysteria, my brain frantically searching for a way to rationalise the man-made miracle which was presented before me. He gave me only a knowing smirk before directing me to the guide whom the Palatium Magnum had graciously appointed to serve me during my stay.

Tuckered into a palanquin carried on the backs of four, dark-skinned slaves, I was finally given a respite from the terrifying spectacle of the City. My heartbeat slowed and my spirit calmed as I welcomed the darkness of the palanquin drapes. But those thick cotton sheets were not impervious to sound and smell, which soon began to fill the confined space of my luxurious transport. In Italia we said that a man could smell a city before he saw one, and that was certainly true for what is left of the major settlements of our peninsula. Constantinople was different, however, for it reeked not only of faeces and waste, but also smelled faintly of incense—a welcome addition to the onslaught of odours which assaulted my senses. My guide, a mellow and well-mannered slave named Ecritius, revealed to me in fluent Latin the source of this unique aroma as we travelled along the main road. Constantinople, unlike the cities of the west, was a true custodian of Christian doctrines as lain down by the saints of yore. A queen amongst cities, her body was wrapped in painted marble glamour and her brows were adorned with twenty one bejeweled crowns, each a church consecrated in the name of God’s incandescent glory. Within the Theodosian Walls there lived five hundred thousand men, women, and children, my dutiful guide explained, scurrying about to earn a living in the shadows cast by these colossal monuments.

Five hundred thousand. Never in my life had I seen that number of anything, much less people. My closest reference point was the ten thousand silver coins in Barium’s war chest, and even that had been hard to grasp. To think that five hundred thousand of living, breathing beings reside within a single city was both absurd and terrifying. It was as if the City itself was mocking my mental predicament, for a chorus of hundreds, no, thousands, of voices, began to fill my eardrums in that instance. Any attempt to identify the source of the sound proved futile, for it came from all around me, and it was both soothing and agitating. A myriad of different tongues, spoken by a myriad of different men, rushed over my dam of reason like the flood of Noah’s apocalypse. I felt the weight of Constantinople pressed tightly against my chest, its unbearable bulk crushing what semblance of self-confidence yet remained in my frenzied mind.

“My lord,” it was Ecritius’s euphonious voice which rescued me from my imminent spiral into madness, “we have arrived at the venue of your residence.” As he spoke the slave pulled back the palanquin drapes, revealing to me the most wondrous sight. Red marble colonnades, each the height of a dozen men, filled my field of vision. Their crimson hue, bright as flame, was sharp against my eyes, and atop each of them stood the figure of a man, no doubt saints and churchmen all, their glass eyes glistening mirthlessly under the light of the midday sun. With raised hands they held up an enormous dome, painted turquoise and furnished with a circle of cerulean panes, it boasted of both unrivalled craftsmanship and wanton excess. Its structure could be likened to that of a monastery, but never in my life had I seen any ecclesiastical architecture endowed with such exquisite beauty. Stepping into the shadow of the columns, I felt as though I was entering not a space of pious learning but the palace of a Persian shah, decorated to proudly display the debauched sovereign’s limitless wealth.

To be continued……

Pingback: The Queen of Cities Part 2: House of God – Veni Vidi Veritatem

Pingback: The Queen of Cities Part 3: House of Man – Veni Vidi Veritatem