“Here is the man whose coming you so often hear prophesied, here he is, Caesar Augustus, son of the Deified, the man who will bring back the golden years to the fields of Latium once ruled over by Saturn, and extend Rome’s empire beyond the Indians and the Garamantes to a land beyond the stars, beyond the yearly path of the sun, where Atlas holds on his shoulder the sky all studded with burning stars and turns it on its axis.”

—Publius Vergilius Maro, The Aeneid

Introduction

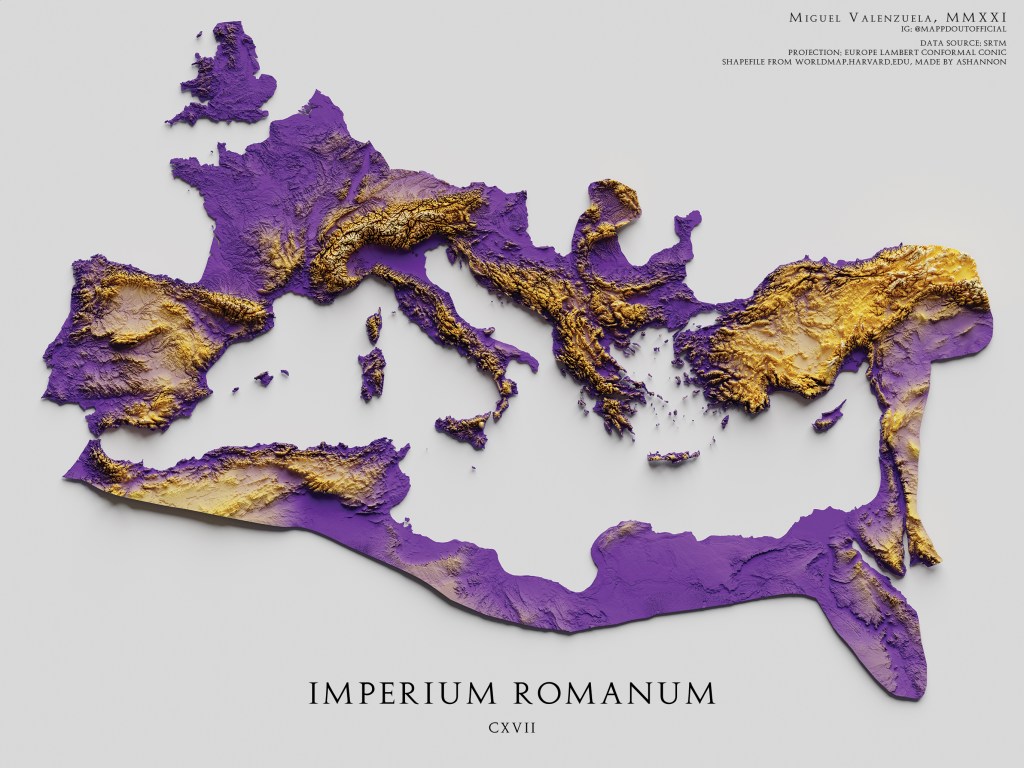

It would be an understatement to say that Imperator Caesar Augustus is a preeminent figure in the study of the ancient world, for it was by his power and grace that the fragmented Oecumene(civilised world) was reforged into one unified polity in the aftermath of the calamitous Roman civil wars of the first century BCE. Like Megas Aleksandros(Alexander the Great) before him, Caesar Augustus had created a new world order in his own image, projecting his imperial authority unto all corners of the earth through statues, cities and cults that proudly bore his cognomen. His personal names, “Imperator Caesar Augustus”, became the supreme titles in the western world—imperial signets that designated one’s mastery over the Roman dominion. For many generations after its creator’s demise, the Augustan model of enlightened autocracy was lauded as the greatest political innovation of Antiquity, a foundation upon which Pax Romana flourished.

It thus seems more than justified for us to ascribe to Caesar Augustus a vital role in human history—the man who restored the Roman Republic and founded amongst the ruins of the Hellenistic Age a new empire that would prosper for another millennium after his passing surely deserves to be venerated as a colossus who rotated the axis of the world upon his shoulders, right? As it turns out, the impact which individuals—no matter how powerful—could have on history, is subject to fierce debate. Ever since history first took on its written form, “Great Men” have dominated its narrative. From Herotodus to Gibbons, historians assign great importance to individuals that acted in the leading capacity during pivotal moments in history. Although this long-standing practice allows us to create relatable points of reference in the primordial crucible of the past by personifying historical events with human figures, it can just as easily obfuscate and distort the reality of what really transpired. The basis of historical knowledge and evidence upon which the science of history was constructed is by nature polluted by political and ecclesiastical agendas, prejudice, bias, and unreliable sources. This churning sea of lies and rumours is the unknowable cosmic chaos upon which all historical research is conducted. To gain new insights on this debate, we must circumvent this writhing mass of darkness which beclouds our vision by defying the fundamental axioms of historical academia, and seek evidence in fiction. Here at VVV, we are commencing a series of writing which examines alternative scenarios that would have unfolded if key historical events transpired in just a slightly different manner, and with the aid of sources both primary and secondary, construct a narrative which traces the trajectory in which history would have developed. By approaching history from an outlandishly audacious angle, perhaps we could gain new insights into whether or not individuals like Caesar Augustus could truly direct the course of human development.

The Antonio-Cleopatrid Dynasty is the first of a series of writing on alternative history, and seeks to examine what could have happened if Caesar Augustus was defeated on the waters of Aktion(Actium) instead of Antonius, and in the process discern how much credit the Augustan regime truly deserves in shaping the world. Our knowledge of what transpired after Augustus’s demise often defines our perception of his life. The immensity of his legacy could therefore be an obsctale which prevents us from viewing the events of the critical first century BC with abject objectivity. Everything is studied with the notion of Augustus’s ultimate triumph in mind, thus it is difficult for us to see the truth. It is therefore my intention to temporarily remove that barrier by imagining a world where Marcus Antonius(Antony) and Kleopatra VII Philopatros(Cleopatra) were the victors at Aktion, a battle from which they emerged as the rulers of the Oecumene. This first post is focused on the immediate aftermath of their victory in the eastern provinces, whereas parts 2~3 will examine the long term implications and impact of this fictional event.

Antony and Cleopatra Part 1: Eastern Administration

As Antonius and Kleopatra’s fleet sailed into the harbour of Aktion, with the banners of victory hoisted high in the evening breeze, the legions which once swore their loyalty to the son of Caesar proclaimed instead their desire to follow Marcus Antonius, the triumphant warlord of the east. In the brutal contest for supremacy in the post-Caesar world, no one deigned to support the defeated. Honour and sacred oaths meant little when Antonius and Kleopatra commanded all the military might of the Mediterranean. The leading figures of Caesar Octavianus’s regime all knew the price they must pay for their blunder, and each travelled to the realm of Hades through means of either dagger or poison. Caesar Octavianus, the man who in another world became Imperator Caesar Augustus, would never see the day of his thirty-second birthday. He merely joined the long list of late republican Roman warlords—Sextus Pompeius, Marcus Lepidus, Titus Labienus, Publius Dolabella, Decimus Brutus—whose ignominious names would be lost to posterity. The world belonged now to the Antonian regime, purged of their enemies and cleansed of all opposition.

But before we can begin discussing how the Antonio-Kleopatrid dynasty was to rule the world, we must first understand the regime of Antonius and Kleopatra. In contrast to popular depictions, Kleopatra was entirely Hellenic, that is, Greek, and not Egyptian. Her dynasty—the House of Lagus(Ptolemaic Dynasty)—claimed descent from Aleksandros, the Macedonian warlord, not the pharaohs of the Nile. She was a Diadochos(successor) of that greatest of conquerors, and bore the Hellenic title of “basileisa(queen)”, much like Aleksandros’s basileios(king). It is also of no relevance what her appearance was. Kleopatra was not defined by her beauty, she did not need to be—she was the most powerful monarch remaining in the Oecumene, and likely the richest individual in the entire world. Ruling from Aleksandreia(Alexandria), the capital of learning, she was renowned for both her intelligence and brilliance—being the first in her dynasty to speak the native Egyptian tongue, amongst eight other languages. Her affairs with Roman generals were products of political necessity, for, although wealthy, Kleopatra was also the scion of a fading dynasty. She was the last Diadochos because all other Successor States had been vanquished and abolished by Rome. The House of Lagus survived only because of their willingness to cooperate with Rome. Kleopatra needed the Romans for their military power, just as the Roman warlords needed her gold. Kleopatra’s ultimate goal was not to rule the world by seducing a Roman general, but to bind the vestigial Hellenic aristocracy which she represented to Rome so that it might survive in the dawning age of legions and emperors. Her powerbase laid in the Nile Delta—the most fertile region in the entire world—and her political capital existed in the form of fabulous wealth and cultural contingency with the Hellenes. Her role in the regime was to organise resources and administer the provinces, for in that task her dynasty, which had exploited the bounties of the Nile for three prosperous centuries, was the most proficient.

Kleopatra and the Hellenes represented a minority in the regime, for despite Kleopatra’s success, the world still belonged to the Romans, and it was in their hands that true power lay. Antonius, much like his western rival, had an intimate relationship with the Roman senatorial aristocracy, of which he was a member, and it was with that selective class that he formed his leading cast of officers and magistrates. The political needs of Rome were hence also the needs of Antonius. More importantly, however, the military at his command was almost entirely Roman, and in the age of warlords, the demands of the legions came before all else. He therefore by both nature and necessity believed in Roman values and in Roman greatness, and all his actions were means to achieve this end. His role in the regime was to ensure that the various interests of the Oecumene align so that they could continue to function as a somewhat unified polity. He sought to preserve Roman supremacy and his regime’s preeminence by binding himself to the Hellenes, but apart from his methods of governance, there were little distinction between Antonius and Augustus. They were both Roman warlords waging wars for supremacy.

The main difference between Augustus and Antonius was that they represented two distinct approaches to imperial governance. Whereas the former stressed centralisation and unification, the latter leaned towards regional cooperation and cultural integration. These divergent political philosophies were each shaped by the varied predicaments faced by the last two Roman rivals of Antiquity. Augustus governed the west, where Roman culture held primacy as the dominant civilisation that surpassed all others in demographic strength, intellectual sophistication, and economic strength. The Celts, the Gauls, and the Germans were rustic savages compared to the urbanised population of Italia, and thus Augustus governed by simply propagating Roman culture in the form of conquests and colonies.

The same solution was inapplicable in the eastern provinces which Marcus Antonius governed in the intervening years of the Second Triumvirate. Unlike Western Europe, which could be likened to a untamed animal upon which Rome imposed her own civilised way of life, the Romans were the barbarians in the Hellenic(Greek) East, which encompassed all of Syria, Anatolia(Turkey), Judaea(Israel), Koile Syria, Aegypt(Egypt), Iran, Mesopotamia(Iraq), and Hellas(Greece). Basileios(king) Aleksandros(Alexander) had conquered the region long ago, and laid the foundation for the establishment of Hellenic supremacy—a vision which his Diadochoi realised after his death. The existing network of Hellenic or Hellenised aristocrats and population centres, which dominated the Fertile Crescent, as well as the Macedonian imperial superpowers that ruled Aleksandros’s old empire, served to prevent the formation of a complete Roman singularity. The Roman magistrates could not simply sweep over the region and proclaim it as pacified as they did in Europe, for the roots of Hellenic culture grew deep in these lands, and thus the reality of geopolitics compelled them to negotiate with the Hellenes.

Cooperation with the local ruling bodies had defined Roman policies in the east ever since Titus Flamininus defeated Basileios Philip V of Macedon at Kynoskephalae(Cynoscephalae). The triumphant general famously partook in Hellenic festivals and celebrated the freedom of the Hellenes—not their conquest by the Romans—in local fashion. When Scipio expelled Antiochos III Megas from Anatolia and Hellas, he did not impose upon the indebted Hellenes Roman taxations. Lucius Lucullus likewise did not annex the region when he brought low Tigranes and Mithridates, and when Pompeius Magnus marched through the region in triumph, deposing disloyal kings and princes, he replaced them not with Roman magistrates but with a new network of loyal Hellenic vassal monarchs. The Hellenes lacked the military power to oppose Rome, and Rome lacked the cultural superiority to conquer the Hellenes, and so they cooperated—the Hellenes paid tribute in return for protection.

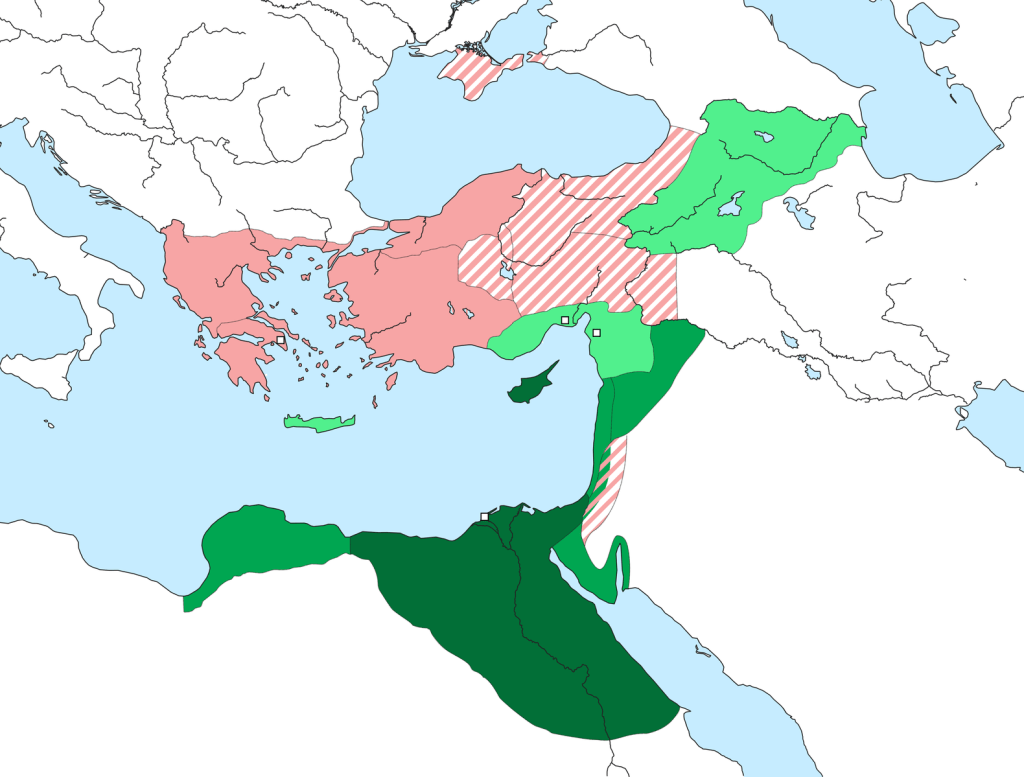

Antonius brought this cultural and political symbiosis to its logical conclusion by binding himself permanently to the vestigial Hellenic aristocracy through its noblest scion, Kleopatra VII Philopatros—the last Diadochos(successor) of Megas Aleksandros(Alexander the Great) and ruler of the last Macedonian Empire in the Oecumene—through marriage. The fruits of their union—Aleksandros Helios, Kleopatra Selene, and Ptolemaios Philadelphos—were all crowned as the basileios and basileisa of the eastern provinces as part of the Donations of Alexandria. Whereas the Augustan regime expelled the last remaining Hellenistic dynasts from the region, Antonius and Kleopatra envisioned a new generation of stronger Hellenic rulers in the east, bound to Rome not just by political necessity, but also by kindred bonds of blood and flesh. Unlike Augustus, who divided the provinces into imperial and senatorial territories, the Antonio-Kleopatrid provinces could be categorised as either dynastic or imperial. Kleopatra, as both the matriarch and as basileisa basileion(the sovereign of sovereigns), would have acted as the overseer of Rome’s oriental dominion, ruling the Hellenistic World through her children. She was to be a new Aleksandros, queen and goddess in one, beloved of the Hellenic people. With her seat of power in Aleksandreia(Alexandria)-by-Aegypt—the wealthiest, most beautiful and erudite city in the Mediterranean, Kleopatra could rule the Orient as Rome’s most important ally. Indeed, her union with Antonius meant that the Hellenic and Roman world could no longer be separated from one another. She was the last and only Diadochos of Aleksandros, and her legitimacy depended upon her husband’s, and by extension Rome’s, preeminence.

The Antonio-Kleopatrid dynasty’s preeminent status in the east would have been emblematic of the continued survival of the Hellenic way of life in the Roman Empire. When Caesar Augustus’s men took control of the Hellenistic World, they destroyed the last bastions of Hellenistic culture with whom the residents of the east could identify. A culture that lacked any earthly representation was always doomed to perish, and from the moment the Romans stripped the Hellenes of a political identity, the demise of Hellenic culture became certain. In time, the Hellenes learned to replace their old symbols with Roman images, as evident in the creation of the cult of Caesar Augustus, which was swiftly adopted by the Hellenes, along with all the Roman rituals and practices of imperial veneration. Roman culture filled the hole left in the Hellenic consciousness by Kleopatra, the last Diadochos’s, demise. In real history, her death marked the end of Hellenic power in the Mediterranean, and severed the bloodline of Megas Aleksandros. Over the next two centuries, the Hellenes began to gradually disappear, each of them converted into Romans after successive generations. 150 years after Caesar Augustus’s passing, there were little distinction between provincial Hellenes and Italian Romans.

Here, history and fiction diverges once again, as Kleopatra’s ultimate triumph in our narrative would have signified both the legitimacy and might of Hellenism in a post-Diadochoi world. Hellenistic monarchs, especially the Diadochoi, associated themselves with the divine, as denoted by their use of Olympian epithets, thus adding an element of ambiguity to their identity. Kleopatra, like her forebears, was simultaneously mortal and immortal, for she was both human and goddess, as realised by statues which depicted her as Isis—one of the premier deities of the Hellenistic pantheon—a fact further reinforced by her status as a descendant of Aleksandros, the son of Zeus. She thus both literally and figuratively embodied the Hellenistic identity of the Hellenic peoples, and her ascendant position within the Roman Empire would allow for the Hellenes to retain both their pride and their culture in the new Oecumene. When Kleopatra took her own life following the victory of Caesar Augustus, the Hellenes lost their last political advocate, and gained in her stead the magistrates of Rome. In this alternate world, Kleopatra’s preeminence would ensure the preservation of Hellenism under Roman hegemony. Whereas the world created by Augustus’s regime was singular, the dominion of Antonius and Kleopatra was to be bipolar—one in which Romanism and Hellenism could thrive alongside each other. The harmony between the two civilisations that had been merged into one polity would hold for as long as Antonius and Kleopatra ruled. And if they could implement the right policies by establishing both Roman colonies in the Orient and Hellenic colonies in Europe, cultural hybridisation would have progressed far enough by the time of their deaths to sustain a peaceful coexistence between Romans and Hellenes without their vigilant stewardship.

The direction of Roman military expansion under the Antonio-Kleopatrid regime was also to be divergent from that of Caesar Augustus’s. Augustus’s power base was located predominantly in Gaul and Italia, whose populations formed the legions with which he fought the civil wars, and thus his focus remained on the western frontiers, where he sought to gratify his benefactors with spoils and security. The Antonio-Kleopatrid dynasty was, on the other hand, built in the east, and although it comprised almost entirely of Romans, the economic strength of the Fertile Crescent was the backbone of their regime. The western provinces were therefore far more hostile and untrustworthy in their eyes, for they had denounced and betrayed Antonius and Kleopatra on the eve of the last civil war, pledging their loyalty to Caesar Augustus so that he might carry out the destruction of Kleopatra, whom they had voted to declare a public enemy. Kleopatra herself was also ideologically incompatible with the west due to her status as both a Hellene and a woman. Roman misogyny and xenophobia had been potent weapons which Caesar Augustus wielded against his rivals. It is thus likely that the Antonio-Kleopatrid dynasty would choose to operate extensively in the west. Rather, to both appease their constituents and to protect their most important assets, the Antonio-Kleopatrid regime must expand eastwards into Parthia. Kleopatra’s expansive network of vassal rulers provided the perfect launching pad for a prolonged campaign against the Parthians who had taken control of Mesopotamia and Iran. The Romans had first clashed with the Parthians when Marcus Crassus led an attempted conquest of Mesopotamia, which ended in one of Rome’s greatest military disasters. Gaius Iulius Caesar had planned a campaign of vengeance against the nomads before he was assassinated. Marcus Antonius himself also suffered defeat and humiliation at the hands of the Parthian when he foolishly tried to conquer Armenia in 40 BC. Now that he had the entire empmire’s resource at his command, could he bring these fierce Eurasian nomads to heel? To be continued……

Thank you for making this far. Writing this post has been particularly difficult as I must simultaneously combat long-standing misconceptions of both Antonius and Kleopatra, as well as establish a historically authentic system of nomenclature and include enough information about the historical context of the Hellenistic Age so as to not cause confusion. Please consider subscribing, sharing, liking, and commenting if you enjoyed it, or if you didn’t, please contact us to tell us how you would like to see us improve. All the photos included are linked to their original artists if you wish to take a glance at more of their art. Look out for the second part of this series, which focuses on the military situation of the Roman Empire and is coming imminently.